The Research

Abstract

We surveyed 189 females who had ingested their placenta and found the majority of these women reported perceived positive benefits and indicated they would engage in placentophagy again after subsequent births.

Our survey shows that the vast majority of women in our sample who engaged in placentophagy did so in the belief it would provide benefits to themselves (and their babies) after delivery. These expected benefits included improved mood and lactation in the postpartum period, among others. Our survey participants generally reported some type of perceived benefit from the practice, felt that their postpartum experience with placentophagy was a positive one, and overwhelmingly indicated that they would engage in placentophagy again after subsequent pregnancies. The most commonly reported negative aspect of placentophagy regarded the nature of the placenta’s overall appeal. While a small percentage of our sample (24%) reported some other negative association with placentophagy, even the women who noted these negative aspects responded that they would engage in placentophagy again if given the chance. This suggests that women could derive some perceived benefits from placentophagy without experiencing negative results unpleasant enough to dissuade them from this postpartum practice.

Conclusions

There was a notable lack of negative side effects of placentophagy reported in the survey, with only a small percentage of women reporting the negative effect of unappealing taste or smell of placenta/capsules. So while placentophagy may be unappealing from a gastronomic perspective, our survey suggests that mothers who choose to engage in the practice do not often perceive negative effects as a result. Additionally, because the overwhelming majority of our respondents indicated that their experience was very positive, this suggests that the negative effects reported were not unpleasant enough to negatively influence their overall experience.

In addition to nearly all respondents indicating a positive or very positive experience with placentophagy, almost all of the participants reported that they would engage in the practice again with the placentas of subsequent children. In fact, both of the participants who selected negative or very negative to describe their placentophagy experience also indicated that they would engage in placentophagy again.

References

Abstract

The use of placenta preparations as an individual puerperal remedy can be traced back to historical, traditional practices in Western and Asian medicine. To evaluate the ingestion of processed placenta as a puerperal (about six weeks after childbirth) remedy, the potential risks (trace elements, microorganisms) and possible benefit (hormones in the placental tissue) of such a practice are discussed in this article based on a literature review.

Conclusions

Placental tissue is a source of natural hormones, trace elements and essential amino acids – the ingestion of raw or dehydrated placenta could influence postpartum convalescence, lactation, mood and recovery.

The risk of intoxication from individual intake appears to be low in terms of microbiological contamination and the content of potentially toxic trace elements. However, the mother should be advised that the processing and use of the placenta is her responsibility and that the transmission of infections cannot be ruled out.

References

Abstract

The use of placenta preparations as an individual puerperal remedy can be traced back to historical, traditional practices in Western and Asian medicine. To evaluate the ingestion of processed placenta as a puerperal (about six weeks after childbirth) remedy, the potential risks (trace elements, microorganisms) and possible benefit (hormones in the placental tissue) of such a practice are discussed in this article based on a literature review.

Conclusions

Placental tissue is a source of natural hormones, trace elements and essential amino acids – the ingestion of raw or dehydrated placenta could influence postpartum convalescence, lactation, mood and recovery.

The risk of intoxication from individual intake appears to be low in terms of microbiological contamination and the content of potentially toxic trace elements. However, the mother should be advised that the processing and use of the placenta is her responsibility and that the transmission of infections cannot be ruled out.

References

Abstract

Human maternal placentophagy, the behavior of ingesting the own raw or processed placenta postpartum, is a growing trend by women of western societies. This study aims to identify the impact of dehydration and steaming on hormone and trace element concentration as well as microbial contamination of placental tissue.

Conclusions

The following average hormone concentrations were detected in raw placental tissue:

CRH (177.88 ng/g), hPL (17.99 mg/g), oxytocin (85.10 pg/g), ACTH (2.07 ng/g), estrogen equivalent active substances (46.95 ng/g) and gestagen equivalent active substances (2.12 μg/g). All hormones were sensitive to processing with a significant concentration reduction through steaming and dehydration.

Microorganisms mainly from the vaginal flora were detected on placenta swab samples and samples from raw, steamed, dehydrated and steamed dehydrated tissue and mostly disappeared after dehydration. According to regulations of the European Union the concentrations of potentially toxic elements (As, Cd, Hg, Pb) were below the toxicity threshold for foodstuffs.

References

Abstract

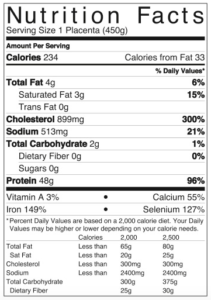

As placentophagy becomes increasingly popular, understanding the nutritional and heavy metal composition of the human placenta has practical implications. Here we evaluated the carbohydrate, sugar, protein, fat, cholesterol, vitamin, and heavy metal composition of the human placenta from uncomplicated singleton pregnancies and found that it contains a significant amount of cholesterol, protein, iron, and selenium, but no detectable levels of cadmium, arsenic, or mercury

Conclusions

Despite reports of placentas containing harmful levels of heavy metals, there was no arsenic, cadmium, lead, or mercury detected within our pooled placenta samples.

References